Students from Lethabong Senior Secondary School participate in group discussions at Soshanguve community conversation

April 21, 2010 – “My status, my health, to protect those I love” was the theme of this year’s second HIV/AIDS community conversation held at Falala Hall in Block F, Soshanguve, last week.

Community conversations form part of the Nelson Mandela Foundation’s Dialogue programme. They give a platform to community members to talk about issues facing them in a free and safe space.

We visited the Soshanguve Township, approximately 30km from Pretoria, to observe and record residents as they participated in a community conversation.

The conversation was a follow-up to a previous conversation that had been held in Soshanguve this year.

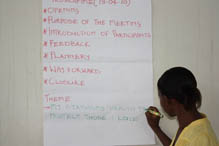

The conversation kicked off with a welcome and an ice breaker from facilitator, Lindiwe Lebese.

She asked community members to introduce themselves and to introduce people they knew to the whole community.

Community members then had to tell those sitting next to them their names, nicknames and their strengths and weaknesses. This was an ice breaker to get community members speaking freely to each other and to relate better to each other.

Speaking at the event, facilitator Olebogeng Nkoliswa said the aim of the community conversation was to get the community talking and find solutions to issues the community faces.

The conversation gives community members the tools needed to tackle HIV/AIDS in their community. South African communities face issues of poverty, unemployment and substance abuse. What the Nelson Mandela Foundation does, through its facilitators, is go into communities to find out which particular challenges those communities face, and through community conversations, attempt to get the community to devise and implement solutions to these problems.

Facilitators identify “dry grass” areas of the community; taverns, shebeens and other drinking spots. Dry grass areas are those areas where activities that could potentially contribute to the spread of HIV/AIDS occur.

They also identify “green grass” areas, which are churches, schools and community centres, among others. Green grass areas are those areas where the community can be uplifted and get more information to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS and potentially decrease the spread of the virus.

Once that is done a community conversation is convened where the community itself talks about its issues and selects an action committee to make sure that actions decided at the conversation are carried out.

Nkoliswa says: “It is something that needs to be carried through by the community once the conversation is over.”

Even though Soshanguve community members didn’t attend in large numbers, this didn’t hinder the day’s proceedings.

After the introductions, Nkoliswa asked the community members to divide themselves into groups of two. He then challenged them with the following questions:

- When and how did you find out about HIV/AIDS?

- How did you react when you found out?

- What did you do?

- What did you not do?

- What do you think you could have done better?

After much discussion group members each got a turn to answer the facilitator’s questions.

Most of the community members found out about HIV/AIDS between 1994 and this year, through their neighbours, teachers, families and friends.

Though some of them did nothing at the time, the most were curious enough to find out what the disease was about and the effect it had on the people that had it.

The community had mixed reactions to what they found out about HIV/AIDS; they didn’t know what it was about and what it meant. Some were nervous, shocked and in denial, while others thought that being HIV-positive meant death was not far off.

Due to a lack of understanding, some community members assumed that all skinny people with sores had the virus.

In terms of taking action, many of them did nothing. Despite information being distributed, the stigma surrounding the disease continued to grow. HIV-positive people were looked down on and judged, and having HIV/AIDS was immediately perceived as one having being given a death sentence.

Community members recall that they didn’t join HIV/AIDS campaigns, nor did they take time to inform and educate others about the disease.

There was, however, a small number of community members who took an active role in teaching others about HIV/AIDS. These members did this through poetry, drama, public speaking, training and affiliating themselves with structures that support people living with HIV/AIDS.

A Grade 11 student from Lethabong Secondary School, Jessica Hetisani, was among those who took action upon hearing about the disease. She and her mother went to get tested.

“I learnt that you don’t get HIV from just having sex. I learnt that you could get infected through exchanging body fluids and blood from others; this stopped me and my friends from playing with used condoms we found at the back of our house,” says Hetisani

HIV/AIDS activist Sipho Masango says he also changed his “player ways” when he found out about the consequences of unprotected sex.

“I used to have lots of girlfriends, but after hearing about HIV/AIDS I chose to be faithful and commit to only one person.”

Asked what they could have done better, Soshanguve community members were regretful that they weren’t active in HIV/AIDS projects.

Some wished they had taken the matter seriously enough to educate themselves and those around them.

Facilitator, Sello Chauke, did not act until his sister was diagnosed with the disease. He realised that he could not help her until he helped himself. So he learnt more about the disease and this changed his perception on who gets infected.

“I thought I was immune to the disease. I didn’t think it would happen to me or my family members and I had to change my mentality. Living with my HIV-positive sister taught me to be more open-minded towards people who are living with AIDS.”

Senior secondary learner Thabang Moshe learnt about HIV/AIDS when his friend contracted a sexually transmitted infection through unprotected sex with multiple partners.

“I did not want to go through what my friend went through, so I decided to educate and protect myself against AIDS.”

Nkoliswa then put a question to the community members, asking them why the youth displayed higher HIV infection rates than their parents.

This question allowed community members to dig deep within themselves and see what role they played in the spread of the disease.

The youth acknowledged that their attitude towards their parents’ teachings was one of the reasons more young people were dying of AIDS-related diseases.

A representative for learners at Boepathutse Junior Secondary School, Mbali Motshweni, said the youth believe that they know better than their parents.

“We don’t listen to them because we feel that times have changed and they don’t understand our challenges and the culture we live in today.

“Our parents teach us about culture, but they don’t talk to us about sex, so we get the knowledge elsewhere.

“Due to peer pressure and fast-paced culture, the youth become adults before they have had time to be children.” Motshweni says.

“This is evident in the high pregnancy rate, lack of education, the high rate of substance abuse among the youth and the mortality rate.”

She urged her peers to avoid skipping being children in a rush to become adults, and to enjoy their childhood.

“Our parents do all they do so that we can be better people. As young people our conscience needs to be alive, we need to take responsibility for our actions and select the people we associate with carefully,” she concluded.

In closing, Nkoliswa handpicked community members and invited them to the centre of the room, where they held hands symbolising a circle of friendship.

“We may not be family, but as a community we need to stand together and form strong bonds so that when hard times come we can stand in unity.

“It doesn’t take a thousand people to make a change; it takes an individual, so always remember that it’s in your hands to make a difference.”

Looking back on the day’s event most of the community members realised that there was a lot they could have done about HIV/AIDS and there is a lot more to learn.

Reflections

Vusumuzi Emmanuel Mhlanga, facilitator

“Community conversation engages with community members and allows them to discover the answers on their own so they can’t forget.”

Lindiwe Lebese, facilitator

“Today I thoroughly enjoyed myself. For the first time as a facilitator I saw people opening up and talking about personal things that affect them daily. I hope next time more people will come so that knowledge is shared.”

Olebogeng Nkoliswa, facilitator

“I think we are on the right track so far. Even though the attendance was low it was nice to see community members nodding and taking notes at the conversation. I hope that in future more people will come so that slowly but surely the HIV/AIDs message gets out there. It was a great event, our prayers have been answered.”

Njabulo Manunu, teacher and facilitator at Lethabong Senior Secondary School

“The conversation was really interesting and educational. It had a positive impact on my life and I think it will help all the individuals who were here today.”

Jessica Hetisani, Grade 11 learner

“Today was really interesting; I learnt a lot. I wish they had told students from other schools so that they could also get the knowledge that we got today.”

Nokuthula Moyo, Grade 11 learner

“Today I learnt to take responsibility for my life and stop playing the blame game. Change begins within; people need to know that no one is immune to HIV/AIDS. I have been abstaining from a young age, even though some of my friends criticise me, I will continue abstaining until I get married.”

Kgothatso Maphanga, Grade 10 learner

“I was encouraged by today’s community conversation. The conversation today taught me a lot about HIV/AIDS. What I am taking home from this is that we need to respect our parents and listen to them because they know better.”