President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf at the 6th Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture

ADDRESS BY PRESIDENT ELLEN JOHNSON-SIRLEAF

THE SIXTH NELSON MANDELA ANNUAL LECTURE

TITLE: BEHOLD THE NEW AFRICA

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA,

JULY 12 2008

Our revered President Mandela, our sister Graça Machel, distinguished ladies and gentlemen:

What an honor it is to be standing before His Excellency, Nelson Mandela, to deliver the 6th Annual Nelson Mandela Lecture here at Walter Sisulu Square in Kliptown, Soweto. What an honour to follow all the many sterling persons who have given this speech before me.

President Mandela on the occasion of your 90th birthday, I would like to pay tribute to you, a man who paved the way for a new generation of leaders and the emergence of democratization in Africa where, through free and fair elect or other processes, authority is transferred peacefully from one civilian government to another; where issues and hope, not fear for the future, define the national debate; where equality of women is a right and women’s agencies supported and utilized; where governments invest in basic services like health and education, for all; where there is respect for individual and human rights; where there is a vibrant and open media; where economic growth is driven by entrepreneurs and the private sector; where open markets and trade define interactions with traditional donor nations; And finally and more importantly, where leaders are accountable to their people.

We admire you, President Mandela; for returning justice and democracy to your country, South Africa, and in doing so, for becoming an inspiration for Africans and for peoples the world over. You have taught us that if one believes in compassion for humanity we can all make a difference.

South Africa is a young democracy that has set a high standard for the continent in terms of its focus on constitutionalism, human rights and democracy. In preparation for its democracy, South Africa made strides in institution creation, including enshrining a Constitution with an ambitious and far-reaching human rights agenda and establishing the Chapter 9 institutions, namely, the Human Rights Commission, Youth Commission, and Gender Commission. As part of the democratic process, South Africa strengthened the media and ensured freedom of information. This country, your country, has led the way in establishing principles for an effective parliament, a fair and transparent judiciary and a transformed legal system.

Many Africans draw on the South African experience to infuse thinking about our present and our future. There has been a long history of engagement in African institutional fora, that seeks to craft a more positive future for our continent. South Arica has contributed to this effort in no small measure.

We thank you President Mandela for your foresight and leadership in providing the stewardship to that process, much of which was achieved through collective effort and built on years of sacrifice and yearning.

Our physical presence in Kliptown is also remarkable. When in 1955 the Freedom Charter proclaimed a bold development manifesto for South Africa and confirmed that the benefits were to be shared by “all who live in South Africa” it set a remarkably high standard for the government and peoples of this country. At that time, Kliptown was described as dusty and windy – look at it now! Soweto itself brings both tears and joy – the many lives lost and the many shining lives – for example Tsietsi Mashinini, a leader of the critical student demonstrations, who fled and found safety in Liberia and married one of my compatriots, sadly died before he could see this marvelous time. Soweto has a special meaning for the young people of Liberia, some of them now old, for it inspired them in countless ways. What is more, Soweto has a special meaning for Africa, for here in this place two giants of Africa, two pillars of the African struggle, two Nobel Laureates, yourself, President Mandela and the loved Archbishop Tutu – lived on the same street, worked and raised your families here and became two Nobel Laureates, symbolizing the victory of your struggle.

Praise singer Zolani Mkhiva

Dear Friends, ten years ago, in his landmark speech in 1998 at the African Renaissance Conference in Johannesburg, then Executive Deputy President Thabo Mbeki called for a revival of the African Renaissance; a renewal of the African spirit; the ushering in of a threshold of a new era. In doing so, he stood on the shoulders of many others, women and men, who dreamed and worked for this in years gone by.

He said, and I quote, “the beginning of our rebirth as a continent must be our own rediscovering of our soul, captured and made permanently available in the great works of creativity represented by the pyramids and the sphinxes of Egypt, the stone buildings of Axum, the ruins of Carthage and Zimbabwe, the rock paintings of the San, the Benin bronzes and the African masks, the rock paintings, the coverings of the Makondes and the stone sculptures of the Shona. A people capable of such creativity must be its own liberator from the conditions which seek to describe our continent and its people as a poverty stricken and disease ridden primitives in a world riding the crest of a wave of progress and human upliftment”.

It has been a long and torturous road toward that revival - from the destroyed kingdoms of Mali and Hausa and Yoruba and Benin in the West; Bantu in the Center; Zimbabwe and Monopolapa in the South; from the slave trade and the balkanization of colonialism, from the liberation struggles of Kwame Nkrumah, Sekou Toure, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, Jomo Kenyatta and you Madiba; from the boom of the 60s and the bust of the 80s to the sobering and challenging time of today.

But I do believe that a new Africa is unfolding before our eyes. The African Renaissance is now at hand. It is within reach. It is embedded within the honest and seeking minds of the young, the professionals, the activists, the believers in our continent. Difficulties remain, no doubt, trouble spots abound for sure, and many seek to discredit this process, but we have reached the threshold and there is no turning back from the irreversible transformation.

Let me recall the essential elements of this transformation, the meaningful African effort to move from dream to reality, to relegate to history the legacies of patronage, corruption, lawlessness and underdevelopment.

Collectively, as a continent, there are three major systemic changes in our body polity that will give rise to this transformation.

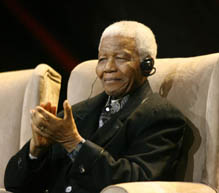

Mr Nelson Mandela greeting the audience at the 2008 Annual Lecture

First, we require much stronger economic management. Second, the resolution of the debt crisis and the changing relationship with our international partners. And third, the shift to democratic and accountable governance.

In the 1980s, almost every sub-Saharan African country faced a macroeconomic crisis of one form or another with high rates of inflation, large budget deficits, and growing trade gaps. These macroeconomic problems are now distant memories for most of our countries. With a few unfortunate exceptions, countries have shifted to much stronger economic policies, inflation has been kept to single digits, foreign exchange reserves have increased significantly. Budget and trade deficits are much smaller than they were in the past, and African countries have created a more conducive environment to encourage private sector participation and stimulate investment, including foreign direct investment. Many countries have embarked on policies that aim at economic diversification.

As a result, Africa’s economic growth has averaged more than five percent annually over the past five years, and for more than half of African countries, this renaissance has continued for more than a decade. This faster growth is not yet fast enough – it is insufficient to effectively combat poverty in many of our countries – but we’ve got to agree that it is a start. It is enough to begin to raise per capita income and purchasing power, and it is far exceeds the zero growth of the past.

The second big change is the end of the three-decade-old debt crisis. Debt began to grow in the late 1970s and the early 1980s following, as we have today, the rapid rise in the price of oil and other commodities. This was made all the worse by government mismanagement. The creditors themselves were a big part of the problem, lending too early large amounts of money to unaccountable dictators who misused and misappropriated those funds, leaving the mess for the next generation to clean up. Accumulated interest from unserviced debt compounded the problem.

The resolution of the 1980s debt crisis has proceeded slowly in distinct stages over the past twenty years. Today, 33 countries have qualified for the first stages of debt write down and 23 of these have completed the process, leading to a reduction of nearly $100 billion in debt. The end of the debt crisis means that improved financial conditions will enable governments to increase spending on health, education, infrastructure and civil service wages. But perhaps more importantly, it also means more independence, ownership and economic management capacity by government authorities who can spend less time negotiating old loans with demanding creditors such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. It has opened the door to defining a new relationship between Africa and its partners based less on old conditionalities and more on strong African leadership, trust, and mutual accountability. The ability of African governments to go beyond and to start to issue country-backed bonds also provides access to more diversified sources of developmental capital.

The third transformation element is political change – the establishment of accountable, transparent and democratic systems of governance.

Sometimes we forget that in 1989, there were very few democracies in all of sub-Saharan Africa. In 1990 Namibia’s liberation set the pace for Southern Africa, followed by South Africa, then Lesotho, and Mozambique. It has spread slowly across the continent – uneasily to be sure and with some reversals, but undeniably reaching many other countries, including my own.

There are today over 20 democracies in sub-Saharan Africa. Consider the transformation – in the space of a generation, democracy in Africa has spread from a very few countries to more than one third of the continent. Some of these are nascent democracies that are still fragile. But for others, the change more clearly prevails. It is hard to predict the future and the change will not be easy or smooth in every country, but never before in world history have so many low income countries become democracies in so short a period of time. Never before has the resolve of African leaders, backed by needed and judiciously used military intervention, ended a rebellion against an elected government in power, as was recently done in the Comoros.

This enormous change engendered by an empowered citizenry has huge implications for Africa and for those few countries that continue to frustrate the will of the people. This New Africa is being built, every day, by the African people – people who reach out across boundaries – real and imagined. They are not waiting for the Renaissance to be determined by states and by governments alone for they know that they are a part of an interconnected world.

And now let me talk a little bit about the country I love, Liberia. It represents a case study of both Africa’s terrible tragedy of the past and the recent resurgence of hope. For the past two decades, the world came to know Liberia as a land of political comedy, widespread corruption and unimaginable brutality. Liberia became that strange footage that flickered on television screens with terrible images of savagery. The Liberian people became refugees and fled to all corners of the globe for shelter. It was a period of darkness and insanity.

Today, the signs of recovery are clear. We are reopening our mines, forestry and oil palm plantations, replanting our rubber, reconstructing our roads and schools and clinics, and restoring our lights and water. Women are being recognized as the agents of the kind of change we must have as they were the first to call for peace in those terrible times. Our children are once again in their smart uniforms on the way to school. Storefronts are open and restocked, and petty traders fill the streets and the roadsides. Families are repairing homes, and construction projects are sprouting throughout the country. Our debt relief program is well underway and economic growth is nearing double digits.

In addition, our Government has taken strong action to combat the scourge of corruption. It is our fervent belief that anyone who uses state power to steer public resources to his/her personal benefit must be held accountable. We are not engaged in this process merely as a gimmick. We are doing it because we are convinced that rampant corruption is one of the key reasons why Africa is unable to deliver basic social services to its people. It is our firm conviction that Africa, indeed Liberia, is not poor, but rather poorly managed. Corruption, exploitation and the misuse of Africa’s resources are central to the inability of African governments to ably and sufficiently respond to the needs of the African people.

In Liberia, we want to end that and our anti-corruption campaign is a measure in that direction. And we are beginning to see results. According to the World Bank Institute, in 2004 Liberia ranked 190th out of 206 countries on “control of corruption” —one of the worst rankings in the world. In 2006 our ranking jumped to 145th. And in 2007 we moved up to 113th. In three years we have moved up 73 places. I am not yet satisfied. Corruptions is still there. But I am pleased that our efforts are beginning to pay off.

Yes, Liberia is on the rebound. Corruption is still there. I know that we are faced with enormous challenges. Yet, we recognize that to be successful, we need to implement policies aimed at both political stability and economic recovery that are mutually reinforcing. We also know that to sustain development over time we have to rebuild institutions and invest in human capacity.

We are equally aware that for Liberia to be successful, we cannot simply recreate the institutions and political structures of the past that led to widespread income disparities, economic and political marginalization and deep social cleavages. We know that we must create economic and political opportunities for all Liberians not just for a small elite class and ensure that the benefits from growth are spread more equitably throughout the population.

We know that we must decentralize political structures, provide more political power to the regions and districts, build accountability and transparency into government decision making and create stronger systems of checks and balances across the three branches of government.

In the short term we must meet the current crises of high commodity prices and widespread youth unemployment that threaten to wipe out the gains that we have achieved.

We know that despite the obstacles and strong resistance to change, despite the risks implied, we must stay the course of reform. Although primarily responsible, we also know that we cannot do this alone and we ask for the continued support, good wishes and care of all of you who are here in this room.

President Mandela, Your Excellencies, distinguished ladies and gentlemen, I am all too aware, that the African Renaissance could come for some and not for others. But that does not have to happen.

As President Mandela remarked in London on the occasion of his 90th birthday; our work is far from over, there is much that remains to be done in the fight against injustice.

We must never forget that the Renaissance calls for a better distribution of the benefits of economic growth; that opportunities must be made equal to enable more Africans to rise above absolute poverty; that more of the poor should have access to health and education, to clean water and electricity and housing.

We must never forget the hundreds of thousands of people, primarily women and children, who continue to die from physical assault and starvation in Darfur.

We must never forget the forgotten people of Somalia who are made victims of violence among competing warring factions and political interests.

As I stand before you today, I would be remiss if I did not express my solidarity with the people of Zimbabwe, as they search for solutions to the crisis in their country.

I recognize my limitations to express views on Zimbabwe. After all Liberia is in West Africa. Liberia is a country of only 3.4-million people. We are thousands of miles away from the realities of Southern African politics. Liberia did not suffer under British colonial rule; nor do we have the same challenges with land distribution that has created so much internal turmoil.

But I am, I hope, part of the New Africa; an Africa rooted in many of the values demonstrated by you, President Mandela. In that Africa, all Africans have responsibility for our collective future. It is therefore my and our responsibility to speak out against injustice anywhere.

This is why on June 30, in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, on the occasion of the 13th Ordinary Session of the African Union, I, along with several other African leaders, spoke out and appealed to colleagues to denounce the run-off election in Zimbabwe. I explained the Liberian experience. In 1985, Liberia held a sham election that was endorsed by Africa and the world. Thirty years of civil war and devastation followed, with thousands dead and millions displaced. It need not have happened.

We cannot lose sight of the fact that we in Africa do not have the luxury to enclose ourselves in our respective political enclaves. Our national policy process must be cognizant of the region in which we find ourselves. That is why it is important that our national public policy processes take into account what is happening in other places, by reflecting our regional and continental conditions.

In Liberia, we know only too well that all war conditions in our country were exported to the region and still today the region continues to suffer as a result. That is why we continue to be concerned about developments in the region. No matter what progress we make in Liberia, if Guinea and Cote d’Ivoire and Sierra Leone are not settled, Liberia will not be settled. Similarly here in Southern Africa, until the situation in Zimbabwe is resolved, the entire region will feel the effects of instability, and the dream of democratic and accountable government will remain unfulfilled. President Mbeki, as then Chairman of the Organization of African Unity, was instrumental in putting Liberia on the road to peace and we think him and we pray that he will do the same for Zimbabwe.

President Mandela, I am often asked what I think my legacy will be, and I reply that this is for historians to decide. But it is my hope that when history passes judgment on me, it will not just remark that I was the first democratically elected woman president in Africa – although I do believe, I am convinced, that women’s leadership can change the world!

I would like to be remembered for raising the bar for accountable governance in Liberia and across the continent; for designing institutions that serve the public interest; for turning a failed state into a thriving democracy with a vibrant, diversified private-sector-driven economy; for bringing safety and voice to women, for sending children back to school; for returning basic services to the cities and extending them to rural areas.

My primary challenge then is to create the institutions that will stand the test of time; that will be there for my grandchildren’s grandchildren. For too long, those watching Africa have focused on personalities, relying on one person, too often one man, to lead the way. But this is mentality has failed Africa, undermining accountability and constitutionally-defined government.

If we were to expand this to Africa as a continent, there is much to be done to ensure that we have pan-African institutions for dialogue, problem-solving, vision setting and programmatic delivery. We need to build regional programmes that provide a platform for intellectual engagement and civic participation that can unlock the potential of all sectors of society.

Let us together reignite a pan-African consciousness and awareness that draws on roots and traditions but is updated and made relevant to today’s Africa.

At a practical level, if we can approach our negotiations with development partners from a consolidated position, we stand a better chance of improving our investment and trade regimes. The proud history of South Africa’s trade union activism – using collective strength and voice – can be used on a larger scale elsewhere.

We can strengthen a development programme for Africa, based on values such as citizen participation and democracy, gender equality, social justice, Integrity, ethics and human rights if we work together.

When you won the elections, President Mandela, dreams were born. Africans dreamed of the end of the exploitation of the past. They dreamed of having dignified economic opportunities to provide for their families. They dreamed of sending their children to decent schools. They dreamed of an end to gender disparities. They dreamed of competent governments that were accountable to the people. They dreamed of national reconciliation and national unity. And they dreamed of living in peace and security with their neighbors.

If someday I am remembered as one of the many dreamers who came in your wake who, unable to fill your shoes, walked in your shadow to build a New Africa then I can think of no other place to be in history. I can think of no better way to be remembered than one of those dreamers who following President Mandela said with confidence that the African Renaissance, the New Africa, is at hand.

President Mandela, We salute you and your legacy. Happy Birthday.

Download the full speech in pdf format, by clicking here.