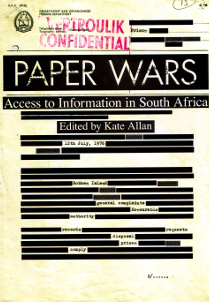

Paper Wars: Access to Information in South Africa was launched on Mandela Day

July 21, 2009 –Mandela Day was not only a day for South Africans to get involved in community-based activities; it was also an appropriate day for the launch of Paper Wars: Access to Information in South Africa, a book that explores the contested terrain of access to information in post-apartheid South Africa. The Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and Dialogue had provided research support to the book.

The book, which is edited by Kate Allen and features a chapter by Verne Harris, head of the Memory Programme in the Centre, uses the experiences of the South African History Archive (SAHA) to highlight the complexity of accessing information after 1994.

The launch, which took place at Boekehuis in Melville, Johannesburg, on July 18, provided the opportunity for the public to engage with the authors on the main issues explored in the book.

Paper Wars, which is published by Wits University Press and SAHA with the support of Atlantic Philanthropies, shows that despite the progressive nature of the Promotion of Access to Information Act, those requesting information often face significant obstacles when attempting to access records.

This is in direct contrast to the promise of transparency and openness of our democratic government. “Access to information is a responsibility of government,” says Piers Pigou, contributor to Paper Wars and former director of the SAHA. “The Department of Justice needs to inculcate a culture of openness and transformation.”

Paper Wars provides four reasons for why government makes it so difficult to access information: resilient cultures of secrecy; the lack of resources to deal with requests for records; cultures of fear associated with making these records public; and poor recording-keeping in government.

Harris, also a former director of SAHA, argues that while the access legislation is an excellent instrument highly thought of internationally, lack of political will to make it work for people has hampered implementation.

Government structures have obstructed access to information in numerous ways, from blatantly ignoring requests to delaying the application process and even denying that certain records exist. Another problem SAHA has experienced is that government departments often use the legislation as a barrier to access, rather than adopting the presumption of a right to information.

Despite these challenges, the legislation does work. “SAHA’s experience has been that the Promotion of Access to Information Act does work,” says Harris, “but you need to have access to [the relevant] expertise and a lot of money to make that happen.”

According to Allen, SAHA has often only been able to access records and information after lengthy legal processes. “Basically SAHA was put in a position that we had to litigate to access the records, and we were doing that time and time again,” she explains.

However, she does offer a word of hope: “Some cases show that by making requests you can change processes, put in place processes to reform structures, people and cultures.”

Allen believes Paper Wars’ significance lies in the fact that few organisations are actively working in the field. As such, the book offers a “persuasive account” of the process of accessing information, identifying trends across departments and offering lessons in overcoming some of the challenges. It should, she says, prove useful for those looking to use the legislation.

Says Harris: “The purpose of the book is to document the early experience of freedom of information in South Africa. It is about the lessons learned, about what works and what doesn’t, and hopefully this will become a tool for using the legislation effectively in future.”