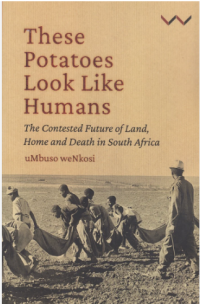

Human wellbeing, it could be argued, is unimaginable without a lived sense of belonging somewhere; of having a place one can call home and experience as home; of the material and the spiritual dimensions of life being inseparable and equally nurtured. This line of reflection emerged very powerfully for me through a reading of a just-published book – uMbuso weNkosi’s These Potatoes Look Like Humans: The Contested Future of Land, Home and Death in South Africa. It is seldom that a book comes along which at once stimulates one’s mind with its ideas and moves one’s soul with the depth of its feeling and its poetry. This is one of them. It’s a short book; a very accessible text; a must-read for anyone grappling with the task of both imagining and contributing to the making of a just South Africa.

Our Constitution, and the Freedom Charter before it, established the principle that South Africa belongs to all who live in it; to all who call it home. The corollary to this, of course, is that all who call it home belong in a South Africa that is ‘homely’, that is hospitable, that is just. And there, precisely, is the rub. Whatever the Constitution depicts and requires, in reality far too few people experience a South Africa having these attributes. As weNkosi demonstrates compellingly, using the district of Bethal, in Mpumalanga, as a lens, multiple layers of dispossession have placed on a multitude of shoulders the burden of not belonging. They become wanderers in life, vagrants of death, on a journey to nowhere. Theirs is the daily experience of what weNkosi calls “ontological nowhereness”. They are to be encountered in derelict downtown buildings, servant quarters at the back of suburban homes, in sprawling shacklands, urban hostels, RDP houses, labour compounds on commercial farms, and in rural villages. They are everywhere in their nowhereness. They are what Dutch scholar Esther Peeren calls “living ghosts” – those who are excluded, discarded, “othered”. Those who are ghosted by prevailing relations of power.

In his back-cover blurb to the book, the Nelson Mandela Foundation’s incoming Chief Executive Mbongiseni Buthelezi says: “South African political and legal discussions of land dispossession and restoration are mostly ignorant of the full extent of what Black people lost when their land was violently taken. uMbuso weNkosi gives us a challenging new reading of dispossessions and how we might resolve being haunted by the past.” Overwhelmingly, it is Black South Africans and Black migrants who are being ghosted in democratic South Africa. Our country is haunted, weNkosi shows, by too many ghosts. The living ghosts. But also the ghosts of those who have died, especially those who died at the hands of oppressive apparatuses of power. Also, the ancestors, who were cut off from their descendants by dispossessions. And the ghosts of those not yet born. Those children to come who have a right to be born into a home called freedom but for whom instead we seem to be preparing a place teeming with new incarcerations. The making of a just South Africa will not be possible until the voices of these ghosts are heard and responded to. We can go further and argue that justice itself is unimaginable without a fundamental responsibility in relation to these voices. Justice demands that power – the powers that be, democratic or otherwise – stand responsible before these voices.

Which is why the question of land still matters. Equitable access to land – in rural areas as well as urban – has, of necessity, been a priority area for the Nelson Mandela Foundation for nearly a decade now. Madiba dreamed of a just society, one in which everyone has a place, everyone knows that they belong. In These Potatoes weNkosi points out that in what he calls an ‘economic’ view, the key issue around land has to do with who it belongs to. But there is also a ‘spiritual’ view, he argues, one in which the key issues have to do with belonging to the land (and to the ancestors who inhabit and enliven that land). We can speak of land, of property, in a literal sense. But we can also understand it in a more or less metaphorical sense. Land as a symbol of wealth, a symbol of access, of home, of belonging. Land matters, from every perspective and in all views. And, as important, in my reading of weNkosi – almost as a subtext – he shows us that it matters that those who would be called South Africans stop focusing on what aspects of South Africa belong to them, and explore instead the ways in which they belong to South Africa.