This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation, but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

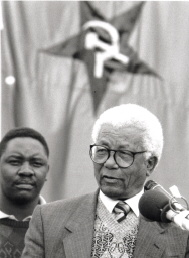

30 Jul 1993: Sisulu, Walter

Click here for more information on the Interviewee

Click here for Overview of the year

POM. Let me start Mr Sisulu with the latest thing that happened here and that was that incident in which there appeared to be an attempt made on your life. From the internal investigation carried out by the ANC does there appear to be a concerted plot to assassinate high level ANC people?

WS. When I was asked that question, "What do you think it is? Do you think it was an attempted assassination?" my answer was, "What else could it be?". I'm not able to say it's a concerted effort. I have not been able to analyse it, to find reasons for it. The behaviour of the Police generally makes it difficult to come to a conclusion because they could harass even without necessarily a plan to assassinate. Let me tell you the background to it. One day three months before it happened we were coming back from a wedding of Gertrude Shope's family, daughter or a son I can't now remember. As we were about to cross the boundary or pass the FNB stadium we came across a roadblock. In a short space of time they said, when they were told it was myself and my security men, "Oh no, go, it's all right. We are sorry." Hardly two minutes passed and they chased my car. They stopped my car and this time came on to search my security men, especially the one that was in front. There was an argument about that and while he was arguing he was waving a gun ready to shoot. The work of this chap appeared to be merely that of shoot when ordered, but they could have done so without order. Others were going round trying to search the cars and then they were told by the driver that the argument was between him and our driver and they came down to say, "We apologise", as if they were learning for the first time.

. I took a very strong exception to this. Without arguing with them I went to see the General who was the Commissioner of Police in that area, General Strauss, he was with Brigadier Pretorius. I explained what happened to me and indicated that my main concern is the danger in the future of this type of behaviour. The fact that they allowed me to pass and then they chased me, I could be taken as a criminal and they could shoot and say, "Well he was running away". They said they would investigate the matter. I heard nothing from them about that.

. When this happened after Mr Mandela's birthday party, it was at about half past one in the morning, we had two cars, one security car, the other one was a friend who usually accompanies us. He has got guns, licence and all that. He's a business man. Now I can't give you the actual order of the cars. My impression was that there was one in front and one at the back. Somehow that was now confused, you couldn't tell which was which - nothing in front, our car now was the leading car. All I know is that I thought we were about to enter the township when we heard some bangs, the sound of guns, bah, bah, and our security man immediately said we must duck. My wife and I did that. I was asking at the same time, "What is happening?" At first my security chap thought it was the usual signal when the police want to signal something, but later on he thought no, it was not, they were mistaken. They saw, this is now this chap who was our security in front, saw the two white policemen, I don't know why they would say police because they say there were no uniforms, and the white car which they were in, a Corolla I think. My wife also saw it. She was sitting on my right and we were sitting together. She said she saw these two whites along our car. Our chaps tried to block that car in order to move it away from us. The security chap said that he saw the wheels of the car turning, that is now the security car which was in front trying to block this car. That's all I know because we were ducked all the time and I was even concerned with the speed of our car because the chap said to the driver, "Speed, move fast."

. When I got home I found the chaps ringing there to report what has happened and I immediately speak to the Brigadier who was accompanying the General when I went there and I said to him, "Well a similar situation to what happened before and even worse now has taken place." And I explained where we were and what happened and he said, "Well I am going to investigate the matter. I will come to you just now." And he did come to me and he said that that car overturned and three occupants were badly injured resulting in the death of the third one and the other one who was in a different car was arrested. He is in the police station, I think John Vorster Square.

POM. This is your businessman friend is it?

WS. No, no, the one at the back. He was actually in the car of the friend, three I think in the car of the friend. Now that's what happened. The following morning I went to a meeting of officials. As we were there the Minister of Police rang and spoke to Mr Mandela and he said, "Well I thought it was you who was involved in this situation and this incident". Mr Mandela said, "No sir", and then he explained. And then he said, "We are taking a very serious view of this matter. We are going to make investigations immediately". I think ten minutes thereafter the Commissioner of the Police, General van der Merwe, rang to the same line, "We've heard about this. We're very concerned. We're taking the matter very seriously. We are going to immediately appoint a Commission." And they did announce later there were two Generals who were appointed. We accepted this but the Secretary General of the ANC was not there. When he came back and he suggested that, "No, we must be part of the investigating Commission", which they accepted. The position is that now. That's where it is.

POM. Still under investigation. But the ANC is part of the investigating team?

WS. Part of the investigating team.

POM. Let me ask you, a year ago you said there had been no change in the situation really since you had been released and Mr Mandela had been released and the ANC unbanned. Would you say that in the last year there has been a change in the situation?

WS. No, I don't know in what context I would have said that because change there was. The very fact that we were released was a change. The fact that the people from abroad were coming back was a change. But perhaps if one was asking me, "Do you see a change since you have been away?" then my attitude would have been, "No, no change, the position is as it was. Apartheid is alive and all that type of thing", but change there has been. The very fact that we are now negotiating and we did so not because of the wish of the government. The negotiations came about because of the work done by the movement both at home and internationally and people who were so vigorous in expressing their intention never to negotiate were now negotiating. That was a change. The violence accompanied the change, our attitude had been and still is that the regime does want a change but the change they want, they want it on their own terms. The fact that we have moved them away from that to begin to be more realistic is the type of work we have done. But they undertook something which was perhaps beyond their capacity, they didn't realise how far it would go. But I think that they are committed but they still want to retain power somehow.

. That is the situation now and we were very angry with the fact that the question of violence which was likely to destabilise everything was being treated in a very cavalier fashion by the present regime. That, and we have been at the government all the time, "You are not doing enough", or, "You are not doing anything at all about violence". How would it be that people, fifty people are killed and not one person is arrested? To us that was an indication how light-heartedly the matter was handled by the regime. A bit more seriousness has taken place in the last one and a half years, I think particularly when the regime wanted a summit meeting and we accepted it but on our own terms.

. We now had to find a way of preparing for a summit in order that it should produce results and we think that way we did succeed because now the regime finds itself quite committed. For instance, on the first summit I am now talking about it was agreed that agreements which are reached, whatever the other people are saying, it's an agreement, it's a contract between us and them. That has helped a great deal and that is what brought about hostility between the government of De Klerk and Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

POM. When you look at the proposals that the ANC had on the table at CODESA 2 before it collapsed, in what way, if any, do they differ from the proposals that they have on the table at the negotiating forum?

WS. Well I think at CODESA 2 there was quite a grave seriousness on that, but I think the seriousness was noticeable after the summit I have referred to, the summit between the regime and ourselves. Now the government was committed. They were committed with the agreement which we made.

POM. Is this the Record of Understanding?

WS. Record of Understanding. They were now committed. It was something quite serious. I think from that time on there was a completely changed situation. CODESA 1, the manner in which the regime handled it, I think they were still looking for a way out. They wanted still to take us for a ride because when it finally came to an end it was clear that what they were interested in was to continue to be in power. There was no question really of wanting to transfer power. But I think, after CODESA 2, after the boycott and after the Record of Understanding, a new situation was created.

POM. Do you think that the government now accepts that this is a process about the transfer of power and not, what they have said all along, power sharing?

WS. Well they used power sharing and we also used the power sharing in a way, but not meaning the same thing. When they were talking about power sharing at that stage they really wanted some form of control, in other words some share of power. I don't think that they still insist on that. I think that they have been shifted from that point of view. I think the discussions that are taking place are serious from every point of view. We are not in agreement in every sense but I think we are marching forward. There is that difference now. The decision to announce the date for elections was a very serious thing and very important. We brought it about. The decision now to work for the Transitional Executive Council, the establishment of that, I think is also serious. They are working on that quite seriously. These two things mean a way forward.

POM. Negotiations are about give and take. When you look at the last year can you point to concessions the ANC made in order to move the process forward and concessions that the government made in order to move it forward as well?

WS. The government obviously moved away from their attitude where they wanted to hear nothing about interim government. They wanted to hear nothing about a Constituent Assembly. They were bent on that. These two have been accepted and they have now become part and parcel of the machinery. We have perhaps made one concession, the decision which is sometimes called, the government would call it, a government of national unity. The government more or less accepts it as nearer to the question of sharing of power, but we don't mean the same thing. The very fact that we have taken that line is some concession to the government, to give the government an assurance that we don't just want to take power. We wanted a new situation created in South Africa and we should do it together and I think in some way it also helped them to see the situation in a different light.

POM. Mr de Klerk, I think, made one big concession and I know that he was quoted in the Financial Times in late June as saying that he saw power sharing as something that would have to be entrenched in the constitution and then three weeks later they dropped their whole motion of power sharing and began to talk about coalition governments and things like that.

WS. Yes, well they dropped it because - what I'm trying to say is that they had a certain conception of what power sharing meant. Power sharing, as far as the government was concerned, that they still really remain a dominant factor and we didn't mean that at all. They spoke of rotation of presidents. We were not prepared to hear that type of thing. That indicated the breaking of the new situation. I think they have finally now accepted power sharing, the government of national unity as the only thing we mean we are serious about and we consider it a concession and we also wanted to break the old perceptions they had. So I think a new situation has been created from that.

POM. When you look at the draft constitutional proposals that came out of the negotiating forum and that were tabled last Monday, on a scale of one to ten how pleased are you with them in terms of how they are meeting your key objectives? Would you give them four out of ten?

WS. No, I think we have not moved fundamentally away but on the other hand we have been flexible in accepting the draft constitution in that it does meet us much as we wanted it. On the other hand we were also opening up a way, but on the question of regions they were too adamant about it. But it depended how the draft was on this question of the power of the regions.

POM. Do you think the draft was giving too much power to the regions?

WS. Well a compromise has been to really meet them half way, to meet the government and the other forces. Our aim was to move them forward and I think we have done that without moving away from the fundamental issue that the central power must stay in the hands of the government. Regions must have autonomous powers as long as it does not tamper with the central power of the government.

POM. So, just to ask the question again, how pleased were you with that draft and did you say, well this at least meets half of what our objectives were or 70% of them, or 80% of them or we're really pleased, we're not pleased?

WS. Well I won't be able to answer it on basis of percentage, but I would say that we thought we had covered ourselves, but at the same time we are giving away some powers to get people to move, to feel that they are really a part and parcel of the negotiations.

POM. Last year you put great emphasis on the question of the youth. You said that one would have to move rapidly or else no-one would be able to control them. In the last year the youth seem to have gotten more out of control than ever. There were 500 people killed in July, I think the largest number of people killed in any month since August of 1990. It looks as though large areas, I go into the townships and now people who used to take me in won't go and when I say, "Let's go in there", they say "Don't go". I ran into a couple of roadblocks in Thokoza last night and the night before and people seem much more on edge in the townships about the youth and what's happening and they don't know whether it's political or gangs or self-defence units or whether it's the ANC and the IFP. What's happening there?

WS. No, I wouldn't say - there's the tendency of wanting to say the youth. Perhaps it may be exaggerated. Violence is not a simple issue. It is very complex. Complex because although fundamentally violence is due to the system of apartheid but there are elements which dominate this violence and we think that it's not even, as people sometimes want to believe, a conflict between Inkatha and ANC. Inkatha is itself in fact being used and it suits them too because they want control as if they can't control it the way they want, then they must spoil everything. But there is a great deal of a third force that is operating. That's a group which is concerned with killing for the sake of killing. They are not concerned with Inkatha, ANC, whatnot, but they want to kill because those are the people who are being paid by the third force to kill for the sake of killing.

POM. Being paid by?

WS. By the third force, right wingers. You see the third force is also not easy to explain. Remember that South Africa has been destabilising the neighbouring countries. How were they doing it? Various methods. Security forces played a very important part in that destabilisation. They have not been moved from that. Our belief is that the security forces, also the police and then the army are playing a very important part in the violence.

POM. Do you think that is true at the highest levels?

WS. Not as in the force as such. I mean it's not a thing engineered by the security heads but within the defence force there are people who have been doing that type of work when they were destabilising Mozambique, Angola and Rhodesia. It was not done by a direct line of command from the top but certain people, for instance, intelligence forces within the army. They are the people who started the situation and who operated in those countries. That is still there. They link up with international forces. You had mercenaries then, you have mercenaries now. Not in the same old way. The point perhaps to grasp here is this, that there are dark forces who are organised and working along those lines. People who do what has happened in the church in Cape Town, once they see progress in the negotiations like now, they then work to undermine it. But you also have neo-fascists who are openly stating their own part, they openly say, "We are now going to disrupt it". They are actually in fact agents of even more sinister forces. Now you have the Generals. These are the Generals who have been operating in the scope which I have just described against the neighbouring states. They now are going to do so to destabilise the very negotiation forums.

POM. Just following up on that, last year after the referendum in March in which De Klerk got this huge vote and took it as a mandate to do what he wanted to do in a way, the right was thought to be dead, that it was finished and yet in the last year the right wing seems to have made a recovery, only 25% of the people who voted De Klerk into power in 1989 would vote for him today. The National Party seems badly fragmented, there are divisions within the government. You have the Conservative Party and the AVU and the AVF coming together and forming, with Bophuthatswana and Buthelezi, this COSAG. What's your reading of what has happened, of this fairly momentous shift in the white population?

WS. In the first place De Klerk failed to utilise the mandate given by the whites. It was a very significant mandate. For the first time the whites of this country said, "We are for negotiation". De Klerk instead, he tried to make speeches, aggressive speeches, continued to emphasise the struggle between him and the ANC. He was miscalculating because he thought that was his personal victory and therefore he thought he was now in the position to direct things as he wanted. He was wrong and I think he made a serious blunder in doing so. At the time when he should have gone forward he should have speeded up, worked for the speeding of the transition, he created difficulties and misunderstanding, suspicion grew. As a result the reactionary forces considered themselves now in a better position. They mobilised. Within the Nationalist Party he created divisions in his approach of not being properly informed, of not being clear as to what the whole issue is. And therefore you had divisions within the Nationalist Party. That encouraged the right wing people who were still in doubt, like the Generals who came in. That's where the situation went wrong. It is true he has now lost influence among the whites and he still has the control over the Nationalist Party but he has got powerful forces who are more in fact on the other side than on his side.

POM. Are the ANC concerned about the fact that they may end up dealing with a De Klerk who can't deliver his own constituency?

WS. We are very much aware, we are very much alive to that. We are concerned that we should watch that situation because we may end up with a De Klerk who cannot deliver. We are very much aware of that. We are working in such a way that we must bring along the more enlightened forces within that side. That is why our approach was that of getting all forces engaged in the negotiations, which I think we have been successful in doing. We have brought in even the right wingers to the negotiating table. We have brought in the Bantustans, including the Buthelezis, to participate and to feel the need of participating. But because, of course, some of them are very ambitious and I must say openly that Buthelezi is, when he says the ANC is concerned with power, he is in fact projecting his own position.

POM. Talking about himself!

WS. Yes, talking about himself.

POM. He's projecting.

WS. You see, that's what his problem is. He wants nothing else but power. "Will I be on top? If not then I must destroy." That's Buthelezi.

POM. Now if he stays out of the process and on this issue of sufficient consensus, if he just doesn't accept whatever definition of it is given, he refuses to come into the process, and if the Conservative Party also refuse to come in to the process, stay outside of it, can you go ahead and have an election that's meaningful in terms of it bringing stability to the country or will you be faced with a period of instability particularly in Natal? I suppose the way I could put it is: must you find a way of somehow accommodating Buthelezi in order to make this process ultimately work?

WS. The problem about that is, to what extent? Because unless he gets his own terms, if you allow his own terms then you have not solved the problem. We are keen to bring about the Transitional Executive Council, we are keen to go on with the new constitution. We want to go ahead because unless we take at least some power we are not going to make headway. That situation can go on indefinitely being uncertain. Buthelezi at present, he is the Chief Minister, he gets all the things he wants, he is not in a hurry and the longer it takes the better for him because he is not really for a change. I said that the government was for a change on the basis of their own terms but Buthelezi is even worse, he's even worse. We nonetheless want to use everything in our power to bring them together because we know that if you leave these forces out they will carry on to destabilise the government. But we are not saying that is going to be done at all costs, at any cost. There will be limits to so much time and as you see the constitution is being drafted by technicians, men who will look at it from all points of view. We think we are meeting them in that way. I don't know how to put it to say to you that we are very keen to get them to come along with us.

POM. Because you must be under pressure too from your own constituency. Three years has gone by and you've been negotiating, negotiating. What's to show?

WS. The longer we delay will create a worse situation. Violence is already creating that situation and it's a very difficult question but we are working on it systematically in spite of that. We are not desperate. We want to bring about a government of the country. So far we are in the fortunate position that we are more or less in agreement with the present regime, the differences are small there and we have to take that more into consideration than anything else because with them we can go a long way.

POM. With the Conservative Party, realistically there's not any way that what they want can be accommodated, that you can have an Afrikaner homeland?

WS. No that is certainly out of the question. Fortunately, De Klerk also says, "Out of the question". No question of homeland, no concession there.

POM. So do you see them staying out or do you see them coming in and being the opposition in a Constituent Assembly?

WS. We have this group of Afrikaners who are in, who are participating in the discussions. It's perhaps a small group, it's the group that broke away from the Conservative Party.

POM. Was this AVU?

WS. AVU, that's right. We've got that group. They also want a homeland but at least they are the people who you can try and reason with. Ultimately we may influence even a greater portion of the Conservative whites on this basis. Those we have to work on, even take there, but there is a stage where there is no give and take. What you say is give and take will be take and they take everything.

POM. And Buthelezi is rapidly approaching that point.

WS. Approaching that point. Now we are also watching the situation within Inkatha. This man who talks about so much democracy he is in fact a dictator. It's a one man show. Others are staying there simply because they are at the mercy of Buthelezi. But they are beginning to look at things differently too. We are interested in not going all out and clash with the King, but the King on the other hand is afraid of Buthelezi, not that he agrees with him in everything. So we have got that.

POM. Do you think there is such a thing as a Zulu card that is that Buthelezi is now using the King to place things in the context of this is the Xhosa speaking people trying to destroy the Zulu nation and the Zulu nation must come together?

WS. That's what Buthelezi is doing. He is emphasising the ethnicity aspect and that's why we would want the King to come to terms with him but we know we can't come to terms, he would not find it easy to break away, but at least let him understand the situation. There may come a time when he will have to take a decision.

POM. To go back to the youth again, I think Tokyo Sexwale the other day said that violence was defeating the ANC, that the violence in the townships was getting more and more out of control and neither the ANC nor the government nor anybody else was in a position to control it, in some areas, not all over the country.

WS. I don't share that.

POM. You don't share that?

WS. I don't share that. The mistake of the government and even ourselves is that our analysis of the situation, of the forces, of the causes of violence, the government weakness has been that they don't want to enter that field. They think it suits them but now they're beginning to see that it's not suiting anybody. I think violence would be managed, controlled, let there be a better understanding between us and the regime, let this question of power which I think in the matter of which must take place, the transitional government, when we can show our teeth. We knew that it is going to happen. It's not a thing that is suddenly happening. We expected that type of thing. The nearer you are to the goal the more violence will take place. We perhaps have not been able to explain that sufficiently for the people to understand. They are looking forward to violence suddenly coming down and as long as there are these forces it is not going to, and as long as we have no control over the security forces, so long are we going to be unable to manage.

POM. So joint control of the security forces would be one of the primary items that the TEC will be addressing?

WS. That's right, that's right.

POM. Do you think that if next April the level of violence is still at the level it is at today that you can have free and fair elections?

WS. Free and fair elections, if it means that there will be no violence at all, it's not going to be possible. I'm not talking of the United Nations, not mechanically applying that standard but they must examine to what extent are we able to more or less manage. To say that there has got to be no violence is quite unrealistic.

POM. That's what the west tends to do, it tends to take its standards of democracy, their own elections, and impose them on other countries and it has always struck me that other countries should send observers to the United States and look at their elections and if 30% turnout in elections in the United States if you had an international observer team here and only 30% of the people turned out to vote they would say it wasn't free or fair.

WS. That's right.

POM. Whereas in the United States they would say that's how it's always been. There are different criteria.

WS. You see that is why our friends abroad, the international community, must be thoroughly educated of the situation and understand the situation so that we don't talk about different standards when they talk of elections. We must speak of the same, at least some understanding from us.

POM. Mr Sisulu, thank you for the time, just another ten minutes. The political fallout of Bisho? I was here last summer (July/August) and the stayaways, the marches and whatever and it looked as though in the ANC those who favoured mass action had taken over from those, were winning the day from those who wanted to concentrate more on getting back to the negotiating forum. Did Bisho have an impact where it changed the decision making process in the ANC itself?

WS. No I don't think so. You see the question of mass action had to be considered on the basis of understanding the desire of the people, the impatience of the people. The ANC who were isolated in the negotiations, were busy negotiating and were not giving vent to the feelings of the masses of the people, then the situation will get out of hand. Perhaps to some extent Bisho will also have a part in influencing people to know that you can talk of mass action but you must also have limitations on how far it can go. The people are beginning to accept that something is going to come out of negotiation whereas there was a stage where they were not sure of their own minds. Should we go back to the question of revolution? I think they now have more confidence that by negotiations we will become closer to our aims.

POM. The assassination of Chris Hani, what have been or still are the political consequences of that?

WS. You notice in the question of Chris Hani that was touch and go, touch and go. Anything could have happened. But we ended up by showing that we were in control.

POM. Some people have suggested to me that when Mr Mandela went on television to address the nation it was an act of great symbolism, power had moved, even though Mr de Klerk was in charge of the security apparatus Mr Mandela was in charge of the nation.

WS. Yes, that's right. That is the position. That is the situation which was brought about but there's another lesson to learn there. We were able to control the situation in an unexpected position like that, but can we continue in the same way if anything else happens? That's our problem. From that time on we were more or less the power to reckon with in the country.

POM. Did the government understand the need to speed up the process at that point?

WS. Yes I think they did because the speeding up and setting of a date arises from the demands which were put forward. We said that unless this is done you will see a new situation in South Africa, and they accepted it. They are as much in a hurry for the date, we were unanimous with the regime.

POM. When you go back to the day you walked out of jail and then to the day Mr Mandela was released and the ANC was unbanned, has progress towards democratic, non-racial South Africa progressed quicker than you would have thought then, more slow or is it going at just about the pace you thought it would have to go through?

WS. No I wouldn't say more slow. I think a significant forward movement has taken place.

POM. A significant movement has taken place?

WS. Yes, beyond even our expectations.

POM. If someone had told you when you came out of jail by July 1993 you're going to be on the verge of having a Transitional Executive Council created composed of members of the ANC and other parties which will really oversee the actions of the government and that there will be an election for a Constituent Assembly in April 1994, what would you have said?

WS. No. I certainly would have said no.

POM. Can I just go back on one or two things quickly.

WS. By the way I should say people are impatient. They think that this process, I myself think it is too slow because it could have been faster, but speaking generally if I were to analyse the situation I would not have imagined that we would be in the position where we are now.

POM. This question of sufficient consensus. Do you think Buthelezi has a point? That in CODESA 2 you really had two main groupings, you had the ANC and its allies and you had the government and it's allies and sufficient consensus was when both the ANC and the government agreed upon something, whereas this time round you have three blocs, you have the ANC and its allies, the government and it's allies and you have COSAG and just because the government and the ANC agree on something that it's an unfair definition of sufficient consensus?

WS. If you were to say to me, do you think something could be considered in this regard and whether this should be some re-examination I should say, "Yes". They have made it their target, their bottom line and efforts are still necessary. The question that confronts me is how do you do it? It's a problem of how do you do it. They themselves cannot suggest a way out because the way out may be to say there will be no end to the negotiations. There is that problem. Perhaps there may still be 1% push to meet them. If that cannot help then they must go their own way.

POM. So essentially you are saying we will go so far to bend over backwards to meet your demands, but should you become unreasonable, tough, we and the government are proceeding ahead and you can either get on the train or get off but you are not going to indefinitely hold things up even though there will be risks?

WS. Even though there will be risks, yes.

POM. Well thank you very much. I really enjoy speaking to you.

WS. Well thank you very much.

POM. Will you still be occupying this office this time next year?

WS. I don't think so.

POM. Are you thinking of stepping down altogether?

WS. Yes, yes, I'm going to step down.